What’s holding you back, and why do you let it?

The legless man in the wheelchair made a very strong point without saying anything.

On the way to the gym for a workout, I was bemoaning my situation and wishing I didn’t have to do a 5-kilometer run. My inner monologue alternated between bitching about my tight left hip and outlining the reasons I prefer power to endurance.

You know the drill. I longed for workouts involving movements in my wheelhouse, I pre-made excuses for a poor performance, and I thought about skipping the run in hopes of snatches the next day.

Then the guy in the wheelchair rolled by with a bunch of empty grocery bags as I was stopped at a light. No markets can be found in the area, so he was clearly buckling down for a long haul to his destination.

No bitching. Just getting it done.

After feeling like an asshole for a moment, I drove the final block to the gym with a much clearer head.

Of course the workout turned out to be exactly what I needed. What I suspected would be a lengthy period of suffering was actually a 5-kilometer cruise on a sunny day while surrounded—and lapped—by friends. I did my best, owned my time and got fitter. And I felt grateful that I was able to run.

As I soaked a sweat angel into the asphalt, I found it interesting that a man in a wheelchair had helped me lose my crutches.

What can you accomplish today?

What can you accomplish today?

In CrossFit—or life, for that matter—crutches are those things you use to make excuses for poor performance, absence, lack of effort, a bad attitude and so on. Crutches are your outs when your goats appear, when your rival beats your ass, when you just don’t want to try very hard but still want a good score.

Sometimes it’s a sore body part. Other times it’s stress from the kids or the pets. Or a bad sleep. Or a lack of rest days. Or age. Or the autumnal equinox. Or what the hell ever.

Crutches, in general, are whatever you lean on when you should just write your time on the board and high-five your classmates.

Crutch: “I could have gone harder but it’s my fourth day in a row.”

Crutch: “I won’t PR because I was up all night.”

Crutch: “I crashed in the third round because I haven’t eaten all day.”

The exact attitude you need when you’re dealing with an injury, fatigue, a bad day at work or back-to-back night shifts.

The exact attitude you need when you’re dealing with an injury, fatigue, a bad day at work or back-to-back night shifts.

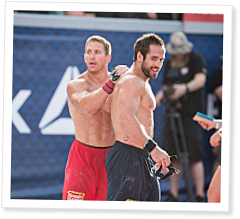

Even legitimate injuries and conditions can be crutches, though truly inspriring adaptive athletes have proven that absolutely anything is possible when you refuse to give up.

I’m not suggesting you should ignore stabbing pain due to a torn knee ligament to do a squat workout.

But I am suggesting you should quit complaining and hit the bench press like you’re training with Ronnie Coleman. Remember that someone has a worse deal and a bigger smile than you do. Move some weight and celebrate with your best “Yeah, buddy!”

More than that, I’m suggesting you should get rid of all your crutches completely. Don’t let whatever ails you derail you. Simply modify the workout as needed, then put your nose to the stone. Cancel the pity party and be happy. Think only about what you can do, push as hard as you can, and earn a score you can be proud of.

Adaptive athletes are proof that limitations are self-imposed only.

Adaptive athletes are proof that limitations are self-imposed only.

Here’s a secret: No one is 100 percent.

We all have stress, soreness, bills, jobs, family commitments, flat tires, plugged drains and a pile of dirty laundry on the bedroom floor. That’s life. You can choose to use all that shit to justify a lack of effort or you can do up your chinstrap and give everything you have that day. I’d suggest the latter, and I bet taking that honorable approach will significantly improve your mood and your outlook on the next workout.

If you’re moping for any reason, lose your crutches by clicking here or entering “adaptive CrossFit athlete” in a browser.

Then head to the gym with a smile and a renewed sense of determination.

About the Author: Mike Warkentin is the managing editor of the CrossFit Journal and the founder of CrossFit 204.

Photo credits (in order): Dave Re/CrossFit Journal, Alex Tubbs, Linette Kielinski